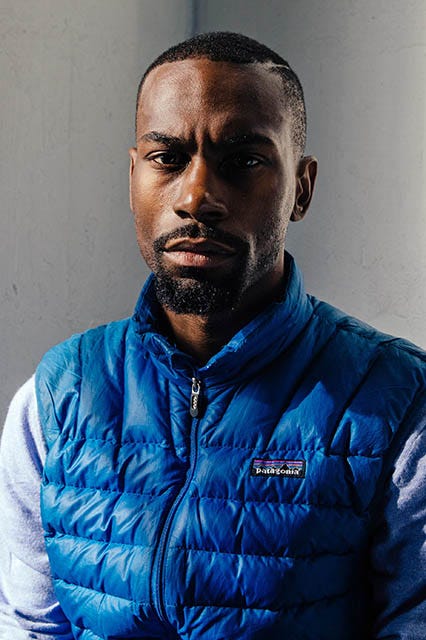

Photographed by Paul Octavious.

Photographed by Paul Octavious.DeRay Mckesson is one of the most recognizable faces behind the push for racial and social equality that became Black Lives Matter.

His leadership and activism, conducted largely through social media, helped coalesce anger and discontent into a movement. From Ferguson, MO, where his activism took form, to Baltimore, his hometown and the site of public protests after the death of Freddie Gray, Mckesson has influenced the discussion around police brutality and racial equality nationwide.

In February, he announced his plans to run for mayor of Baltimore. He plans to bring to that campaign the lessons he's learned about organizing in the digital age.

"What is important to understand is that there are many ways to organize, and there are many people who want to do the work that don't want to be members of something," he told Refinery29. "They don't want to be members of an organization, but they want to do the work. What we have seen is that there's power in that, too."

Mckesson spoke to Refinery29 by phone to talk more about his experience and his vision of a future free of racial injustice and police brutality.

Let's start with your personal journey. Can you talk about how you got involved in activism?

"I've always been involved in issues relating to children and families. I began my work in Baltimore in 1999, training young people how to work together, and I was the chair of Youth as Resources, a youth-led nonprofit in Baltimore. Education was the social justice issue that I was most devoted to. I was a teacher; I was a senior leader in two public school districts. That work was, and remains, really important to me. And then the death of Mike Brown changed my life. For the first time, I understood police violence to be pervasive across the country.

"I was sitting on my couch on August 16; it was about 1 o’clock in the morning. I saw the tweets and I was like, 'I need to do something. I want to go stand in solidarity with the people,' and I went to witness. I got in the car and I drove nine hours to St. Louis. I got tear-gassed on the second day I was there, and it was that moment I became a protester. It was in that moment that I understood that this is not the America that I thought it was, and I was willing to put what I had on the line for the America I knew it could be.

"I was proud to be with people there. The sense of community that emerged in August 2014 remains one of the most powerful things I've ever been a part of. People just came together in a way that was just profound, just really, really important. People were willing to put whatever they had on the line to say that we would not be silent."

Social media allows people to be in the conversation. Is it 'enough'? No. Nothing is. But is it necessary? Yes.

You recently released a multifaceted campaign to end police violence in America, called Campaign Zero. What are you doing with that platform and its 10 "buckets" of issues?

"One of the core messages of Campaign Zero is that change will have to happen across all 10 of the buckets for it to actually change outcomes, for there to be a positive benefit in people's lives. Body cameras without independent investigation, or without fair police union contracts, means little.

"The second message is painting a clear picture for people about the discrete areas that we need to press on to get to change. The two most recent projects we launched were the police union contract project and the police use of force project, both things that I think are important. I talked to President Obama about both of them."

A few days before this interview, you went to the White House and spoke to President Obama — do you think that the administration and government are receptive to discussing the needs of black and minority Americans?

"Yes. I think that now they understand the issues, they've worked on understanding the issues over the last 18 months. The question becomes what will they do about them.

"The way President Obama talks about the issues is better than it was, and I'm interested to see the indication that his administration is willing to work until the last day. They're not going to quietly go into the sunset. I think that there's still opportunity for him to make important changes in the administration in regards to criminal justice and race in policing. It was an hour-long meeting, President Obama extended it for another 30 minutes, and the only questions he took were from younger activists. It was important that we speak directly to the President and not only through his staff, and to hear him respond to the things that we said."

Photographed by Paul Octavious.

Photographed by Paul Octavious.You recently announced that you'll be running for mayor of Baltimore. What made you want to take on that role? What's the value of working within the system versus working outside it?

"This has to be a city that works for people. It has to be. So much of what we've done in protests is tell the truth in public, knowing that that's a precursor to changing the way the world works. Running for mayor is about having a vision and a plan for what the city can be, and being really intentional about that. It's also about pushing the city to be better than it is, and that's important to me. The city I love, this is home; I was born and raised here, my family is from here. The other candidates are more of the same. It is all establishment, it's different variations of establishment, and that just isn't okay. People deserve a city that works for them, and they deserve people who are willing to tell the truth in public, to do what's right by people.

"Working within or outside a system is not an either-or. It's important that people challenge the government to be the best it can be. That is part of what it means to be a democracy, that is essential. It's also important that people do the things that actually improve people's lives — today, tomorrow, and the day after — and we need to think about how to do both of them.

"You should be able to see a plan and hold me accountable to it. That is real. People should see their lives in your plan. The pieces of my plan you've seen are about safety, the economy, and education, and I think all of them are aggressively innovative, that it's all possible. It pushes all of us in the city to think deep about what we expect and deserve. There's no syllable, there's no easy soundbite that encapsulates the amount of change that the city needs to do right by its people."

I love my blackness. And yours.

— deray mckesson (@deray) February 26, 2016

You've been told that you should be more like Martin Luther King Jr. How does that criticism affect your work, and what do you think of the fact that King's legacy of nonviolent protest has been set up as sort of a gold standard for advocacy?

"We did not invent resistance last August, and we did not discover injustice, right? That we exist in a legacy of — so many people fought before us, who have been pressing systems and structures to do right by people. We have things to learn from that. But we also are operating in a time that is different and tools that are different, and that is true as well. So I don't feel pressure to be like anyone who came before us. I am mindful that I have things to learn from those who came before us."

Photographed by Paul Octavious.

Photographed by Paul Octavious.With the changing nature of activism, there's sometimes this idea that if you're doing it on social media, it's not real activism. You've accomplished so much with platforms like Twitter. What do you think of that power of outreach and the new digital face of activism?

"I think that we're just on the cusp of seeing the impact, I think the movement is a testament to the importance of people having the tools to tell the truth on their own and not being mediated by someone else. This is actually really early stages of seeing the power of this. I think that in the next year or two years, we'll really see online communities become even stronger in how they push a host of organizations, governments, companies to do well by people.

"I will never speak badly about telling the truth. For so many people, social media allows them to tell the truth and to hear the truth, and that is a necessary precursor to people acting. Social media allows people to be in the conversation. Is it 'enough'? No. Nothing is. But is it necessary? Yes."

Mckesson isn't doing this work alone. You can check out our other installments of our profiles on Activists to Know to meet world-changing activists behind the continuing fight for civil rights. Charlene Carruthers is making change from a black, queer, feminist perspective, and Carmen Perez is finding the intersections between the issues of criminal justice reform and the needs of women and children.

Editor's note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

You Can Replace Donald Trump With Voldemort — Sort Of

Hundreds Turn Out To Support Trans Child In Small Wisconsin Town

Erin Andrews Awarded $55M In Nude Video Lawsuit